-

chevron_right

chevron_right

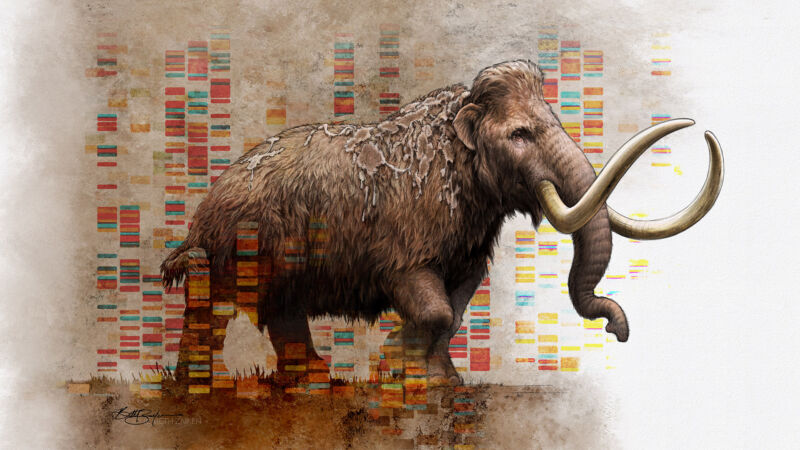

New effort IDs the genes that made the mammoth

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Friday, 7 April, 2023 - 17:40 · 1 minute

Enlarge (credit: Beth Zaiken)

An international team of scientists has published the results of their research into 23 woolly mammoth genomes in Current Biology . As of today, we have even more tantalizing insights into their evolution, including indications that, while the woolly mammoth was already predisposed to life in a cold environment, it continued to make further adaptations throughout its existence.

Years of research, as well as multiple woolly mammoth specimens, enabled the team to build a better picture of how this species adapted to the cold tundra it called home. Perhaps most significantly, they included a genome they had previously sequenced from a woolly mammoth that lived 700,000 years ago, around the time its species initially branched off from other types of mammoth. Ultimately, the team compared that to a remarkable 51 genomes—16 of which are new woolly mammoth genomes: the aforementioned genome from Chukochya, 22 woolly mammoth genomes from the Late Quaternary, one genome of an American mastodon (a relative of mammoths), and 28 genomes from extant Asian and African elephants.

From that dataset, they were able to find more than 3,000 genes specific to the woolly mammoth. And from there, they focused on genes where all the woolly mammoths carried sequences that altered the protein compared to the version found in their relatives. In other words, genes where changes appear to have been naturally selected.