-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Yes, this year is as hot as you think it is

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Thursday, 7 September, 2023 - 20:08

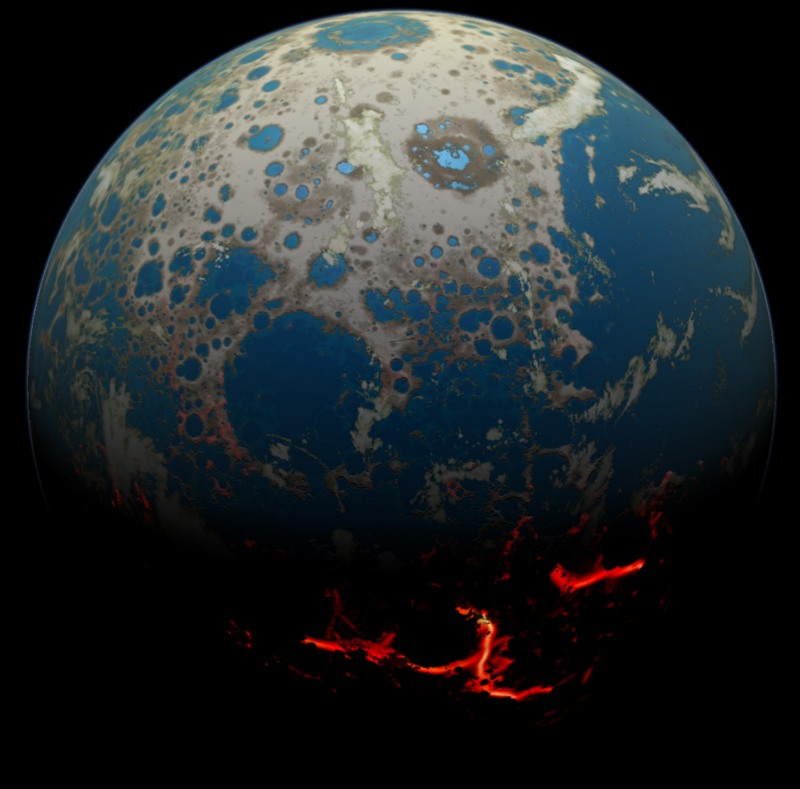

Enlarge (credit: Marc Bruxelle )

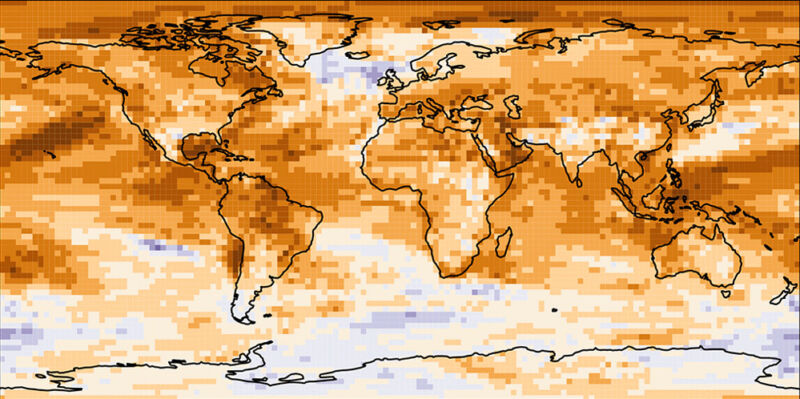

"Climate breakdown has begun," declared UN Secretary-General António Guterres. Guterres is not a climate expert himself, but in this case, he's basing his opinion on the data and analyses generated by the actual experts. If you thought this year was a bit of a weather suffer-fest, it probably wasn't your imagination, as the Northern Hemisphere has just experienced its hottest summer on record, driving the year to date into the second-hottest position.

While the weather isn't climate, the climate sets limits on the sort of weather we should expect. And a growing number of analyses of this year's weather are showing that climate change has been in the driver's seat for a number of events.

Hot, hot, hot

On Wednesday, the World Meteorological Organization released its August data , showing that the month was the second hottest on record and the hottest August we have experienced since temperature records have been maintained. The only month that has ever been warmer is... the one immediately before it, July of 2023.