-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Were bones of Waterloo soldiers sold as fertilizer? It’s not yet case closed

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Wednesday, 10 August, 2022 - 20:00 · 1 minute

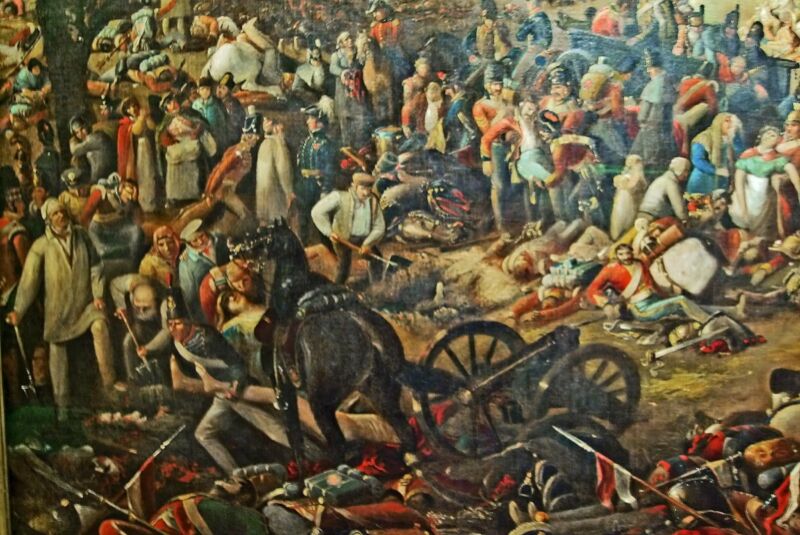

Enlarge / The Morning after the Battle of Waterloo , by John Heaviside Clark, 1816. (credit: Public domain )

When Napoleon was infamously defeated at Waterloo in 1815, the conflict left a battlefield littered with thousands of corpses and the inevitable detritus of war. But what happened to all those dead bodies? Only one full skeleton has been found at the site, much to the bewilderment of archaeologists. Contemporary accounts tell of French bodies being burned by local peasants, with other bodies being dumped into mass graves. And some accounts describe how scattered bones were collected and ground up into meal to use as fertilizer.

It's that last claim that particularly interests Tony Pollard, director of the Center for Battlefield Archaeology at the University of Glasgow. He has examined historical source materials like memoirs and journals of early visitors, as well as artworks, to map the missing grave sites on the Waterloo battlefield in hopes of finding a definitive answer. He recently provided an update on his efforts thus far in a recent paper published in the Journal of Conflict Archaeology.

Napoleon had initially been defeated and deposed as emperor of France in 1813, ending up in exile on the island of Elba in the Mediterranean. He briefly returned to power in March 1815 for what is now known as the Hundred Days . Several states opposed to his rule formed the Seventh Coalition, including a British-led multinational army led by the Duke of Wellington, and a larger Prussian army under the command of Field Marshal von Blücher. Those were the armies that clashed with Napoleon's Armée du Nord at Waterloo.