-

chevron_right

chevron_right

A Victorian naturalist traded aboriginal remains in a scientific quid pro quo

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Wednesday, 29 November - 00:01 · 1 minute

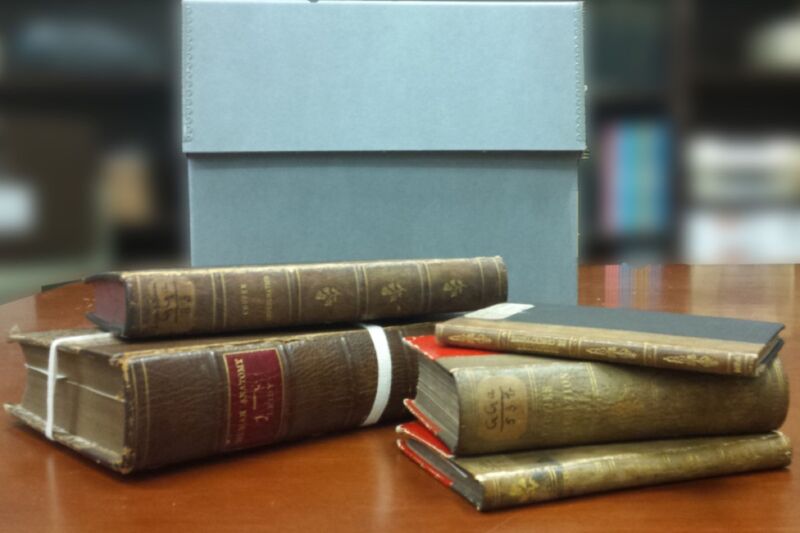

Enlarge / Nineteenth-century naturalist and solicitor Morton Allport, based in Hobart, built a scientific reputation by exchanging the remains of Tasmanian Aboriginal people and Tasmanian tigers for honors from elite societies. (credit: Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania)

When Australian naturalist and solicitor Morton Allport died in 1878, one obituary lauded the man as "the most foremost scientist in the colony," as evidenced by his position as vice president of the Royal Society of Tasmania (RST) at the time of his death, among many other international honors. But according to a new paper published in the journal Archives of Natural History, Allport's stellar reputation was based less on his scholarly merit than on his practice of sending valuable specimens of Tasmanian tigers (thylacines) and aboriginal remains to European collectors in exchange for scientific accolades. Allport admits as much in his own letters, preserved in the State Library of Tasmania, as well as to directing grave-robbing efforts to obtain those human remains.

“Early British settlers considered both thylacines and Tasmanian Aboriginal people to be a hindrance to colonial development, and the response was institutionalised violence with the intended goal of eradicating both,” said the paper's author, Jack Ashby , assistant director of the University Museum of Zoology at Cambridge in England. “Allport’s letters show he invested heavily in developing his scientific reputation—particularly in gaining recognition from scientific societies—by supplying human and animal remains from Tasmania in a quid pro quo arrangement, rather than through his own scientific endeavors.”

Thylacines have been extinct since 1936, but they were once the largest marsupial carnivores of the modern era. Europeans first settled in Tasmania in 1803 and viewed the tigers as a threat, blaming the animals for killing their sheep. The settlers didn't view the Aboriginal population much more favorably, and there were inevitable conflicts from the settlers displacing the aborigines and from the increased competition for food. In 1830, a farming corporation placed the first bounties on thylacines, with the government instituting its own bounty in 1888. (Ashby writes that the true sheep killers were the dogs the settlers bred to hunt kangaroos.).