-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Rare myocarditis after COVID shots: Study rules out some common culprits

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Tuesday, 9 May, 2023 - 22:15 · 1 minute

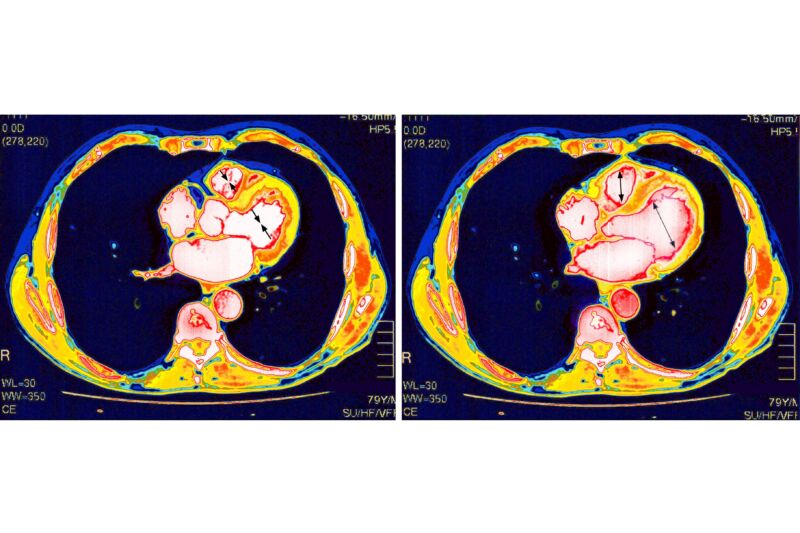

Enlarge / Heart scan. (credit: Getty | BSIP )

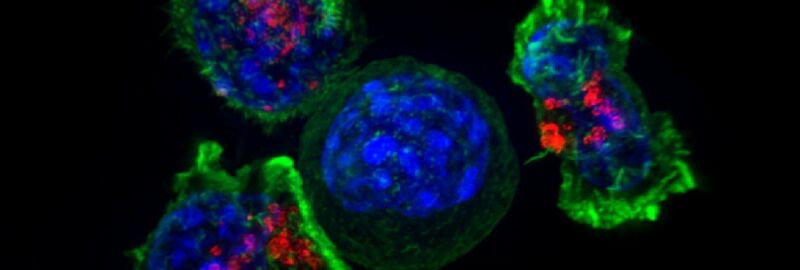

The mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines have proven remarkably safe and effective against the deadly pandemic. But, like all medical interventions, they have some risks. One is that a very small number of vaccinated people develop inflammation of and around their heart—conditions called myocarditis, pericarditis, or the combination of the two, myopericarditis. These side effects mostly strike males in their teens and early 20s, most often after a second vaccine dose. Luckily, the conditions are usually mild and resolve on their own.

With the rarity and mildness of these conditions, studies have concluded, and experts agree that the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risks—male teens and young adults should get vaccinated. In fact, they're significantly more likely to develop myocarditis or pericarditis from a COVID-19 infection than from a COVID-19 vaccination. According to a large 2022 study led by researchers at Harvard University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the group at highest risk of myocarditis and pericarditis after vaccination—males aged 12 to 17—saw 35.9 cases per 100,000 (0.0359 percent) after a second vaccine dose, while the rate was nearly double after a COVID-19 infection in the same age group, with 64.9 cases per 100,000 (0.0649 percent)

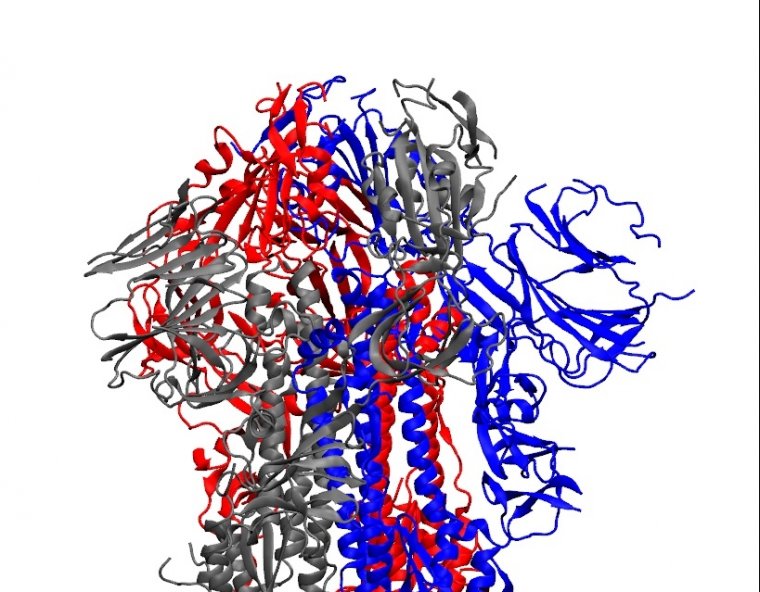

Still, the conditions are a bit of a puzzle. Why do a small few get this complication after vaccination? Why does it seem to solely affect the heart? How does the damage occur? And what does it all mean for the many other mRNA-based vaccines now being developed?