The idea to compress music into digital files started decades ago, but the birth of the MP3 was a breakthrough moment.

The idea to compress music into digital files started decades ago, but the birth of the MP3 was a breakthrough moment.

German engineer Karlheinz Brandenburg and his colleagues first made the MP3 format public in 1993. This made it possible to reduce the size of music files without any significant loss of audible sound quality.

At the time, the music industry was breaking all-time sales records thanks to the CD, but that would soon change.

“System Shock”

Filmmaker Jed I. Rosenberg directed a documentary for Bloomberg called “ System Shock ” which provides an intriguing and insightful overview of how the “MP3” set in motion a series of events that completely disrupted the music industry.

While we recommend everyone to watch all three parts in full, we’ll highlight some quotes in the article below.

After Brandenburg published the MP3 format it didn’t take long before hobbyists started using it to rip CDs. Some people shared or traded these files with friends, which initially happened mostly offline. However, little by little these MP3s made their way onto the Internet.

Music Industry Saw MP3 as an Opportunity

These new developments didn’t go unnoticed by the music industry. The RIAA’s former CEO, Hilary Rosen, recalls that they mostly viewed compressed music as an opportunity.

“In the late ’90s, my staff started monitoring the online space and we really did see a significant amount of interest in MP3 all of a sudden because of its ability to compress a music file.

“I think there really wasn’t any sort of panic in the industry in the early days. My team did look at it and saw it as not really as much of a threat as an opportunity,” Rosen said.

The Celestial Jukebox

In the late 90s, before the file-sharing boom had started, music industry insiders had already toyed with the idea of a ‘celestial jukebox’ that could access all music in the world.

The RIAA realized that with compression, this jukebox idea would move nearer to reality, a position that was shared by others.

“The ‘celestial jukebox’ was a theoretical construct at the time,” Al Teller, a former executive at MCA Records and CBS records recalls. “Every song ever made was gonna be in what we call the cloud right now, and would be instantaneously available to anyone on the planet simply by pressing a button on your gizmo.”

While the music industry ‘thought’ about it, there was little need to innovate at that time. The surge in CD sales resulted in record-breaking revenues year after year, and computers were seen as spreadsheet and word-processing tools by most people.

The Napster Moment

This all changed when a young student named Shawn Fanning came up with Napster. At the time, Fanning and Sean Parker were already sharing MP3s on IRC channels, but Fanning envisioned something bigger. A central database that everyone in the world could access.

To realize this dream Fanning stopped going to school. He set everything aside for months and didn’t stop until the first version of Napster saw the light. That moment came in 1999. Soon after, it went viral.

The documentary shows how millions of people flocked to the new app. Some people, mostly teenagers, were completely consumed by it and downloaded thousands of MP3s just because they could.

The application soon reached the RIAA’s offices too. They were equally impressed.

“My head of anti-piracy, Frank Creighton, came into my office and said, ‘I’ve just found the most fascinating thing.’ It was Napster,” Former RIAA CEO Rosen recalls.

Rosen immediately tried Napster and put in a search for Madonna’s ‘Holiday’ that returned plenty of results.

“I was like, ‘Whoa, that’s pretty amazing.’ That’s like the celestial jukebox. We’ve been talking about this for years.”

After the initial excitement sunk in, Rosen realized that Napster was a treasure trove of pirated content. She reached out to Napster in an effort to have the infringing content removed, starting with the Billboard 200. Napster said it would try to help, but nothing really happened.

Music Titans Were Terrified

In the months that followed, the file-sharing revolution grew and grew. The music industry shifted to panic mode and in February 2000 all major label executives discussed the threat during an RIAA board meeting at the Four Seasons Hotel in Los Angeles.

“I will never forget this day. All of the heads of the labels, literally the titans of the music business, were in that room. I had somebody wheel in a PC and put some speakers up and I started doing a name that tune,” Rosen says.

The major music bosses started to name tracks, including some that weren’t even released yet, and time and again Napster would come up with results. Needless to say, the board was terrified.

“We used to have this line in the record business that there was sort of nothing a good hit couldn’t fix. There was no screw up a good hit couldn’t fix. There was no amount of money lost on a deal that a good hit couldn’t fix.

“I think that was the moment when people said, ‘Ooh, maybe a good hit can’t fix this one’,” Rosen added.

Napster Had Benefits Too

While the big music bosses were scared, others saw opportunities. Not just the pirates, but also artists who used Napster to deliver their music directly to the rest of the world. They included rapper Benefit , for whom Napster was a major breakthrough .

Benefit entered and won a contest organized by Public Enemy’s Chuck D , who himself was a major supporter of Napster. He was one of the first major musicians to argue that this could be good for artists.

“I look at Napster as being new radio and people are finding ways that now you’re going to have a million artists, and a million labels, now all in the record game,” Chuck D said at the time.

The major labels and the band Metalica clearly disagreed and famously sued Napster. This resulted in public outrage including massive protests, but eventually the court decided that Napster had to stop the copyright infringement. The company later shut down its servers, barely two years after the first launch.

Napster Was Soon Replaced

The problems for the music industry didn’t stop there. Soon, new and better file-sharing tools popped up, and these became increasingly decentralized. Fromm Kazaa, through Morpheus to LimeWire, music sharing was suddenly unstoppable.

The problem was that the music industry didn’t really have a good alternative. There was no digital equivalent of the music store yet, as Larry Kenswill, a former executive at Universal Music Group, explains:

“The huge, huge problem at the time is that it was very hard to tell people not to use peer-to-peer methods and they’ll say, well, what should we use? And the answer was, go to a record store and buy a CD. That’s not what they wanted to hear.”

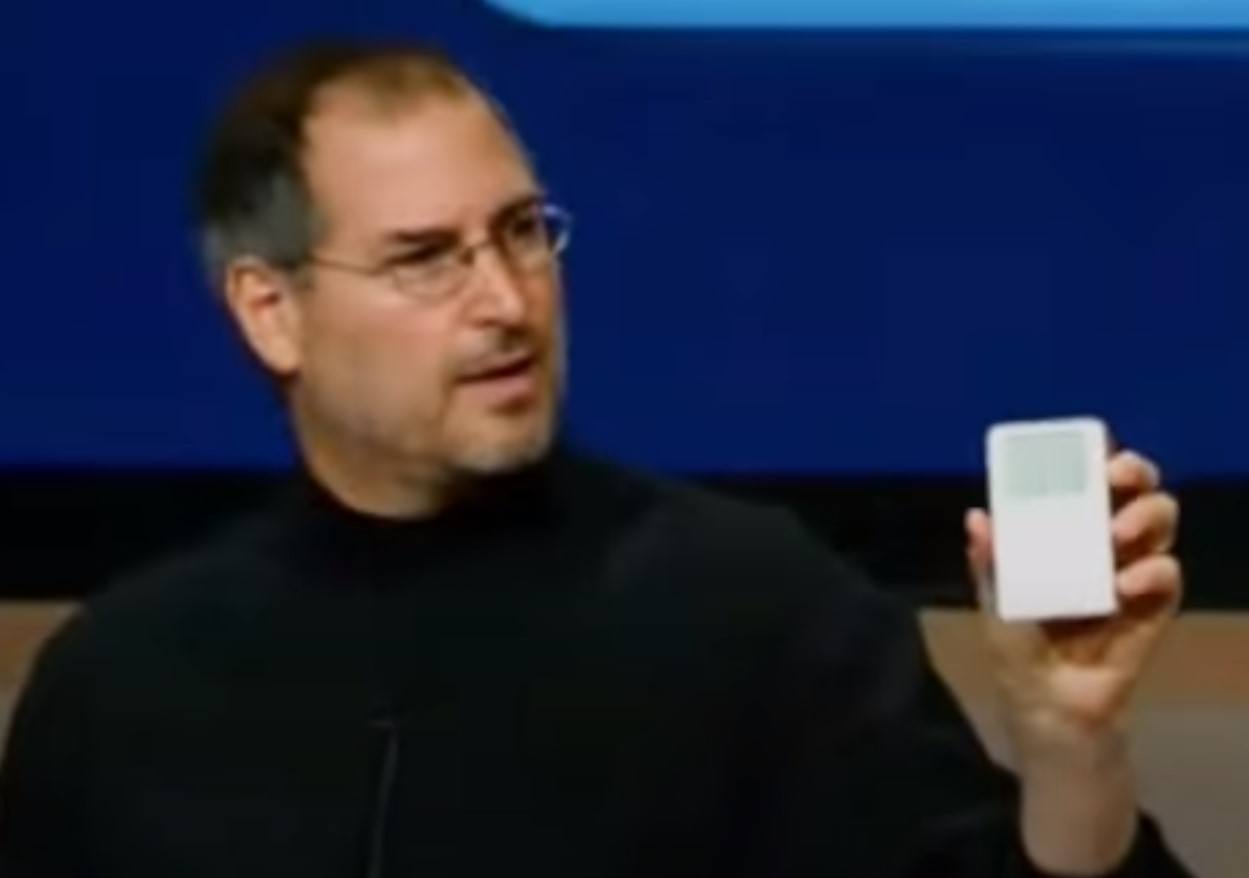

Steve Jobs Has a Solution

The labels were desperately looking for a solution and just around that time Steve Jobs, who had just returned to Apple, entered the scene. Apple had their iPod and was secretly working on its own music store.

In late 2002 Jobs reached out to the major labels to share his plan. Several major executives were invited to Cupertino where Apple’s CEO personally gave an hour-long demo of the iTunes store.

“It worked better than anything we’d ever seen before. And it became obvious this, this was a good thing to go with,” Kenswill recalls. “The one thing of course about the iTunes music store, he wanted every song to be a buck.”

Unbundling the Album

With this demand, Steve Jobs arguably changed the music business more than pirates did. It meant that a song couldn’t cost more than a dollar and tracks would become unbundled from a full album.

While this sounds reasonable today, it was a revolution back then. For decades artists have sold full albums even though many people were only interested in a few tracks at most. This generated heaps of excess revenue. With iTunes, that model changed. And the money too.

“The unbundling of albums meant that the revenue that came in was significantly diminished,” Rosen says.

While much of the decline in music sales revenue has been blamed on piracy, it can be argued that the move to digital downloads and the unbundling that came with it had a much bigger impact. This is something we already argued over a decade ago .

While iTunes did well, there were still plenty of people pirating music. Apple’s store didn’t provide the ‘celestial jukebox’ experience pirate apps had, simply because most people could not afford to fill up their MP3 players legally.

RIAA vs. The Public

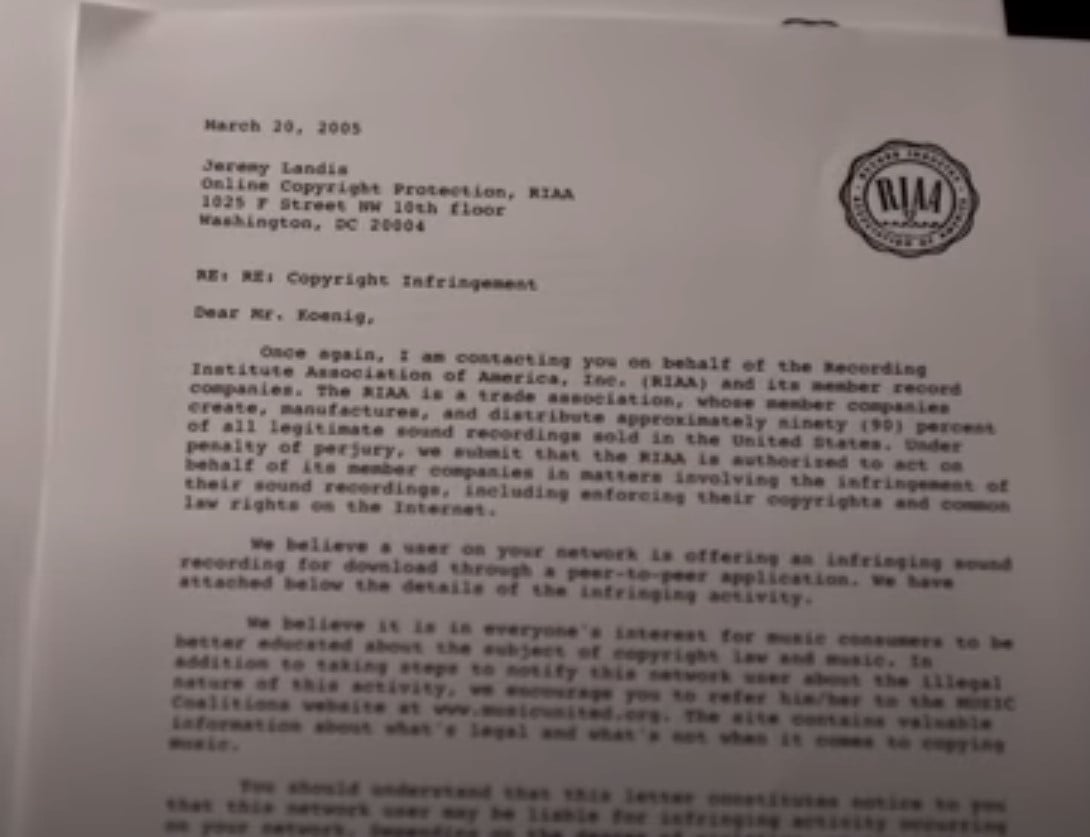

Faced with a rampant music piracy boom the RIAA decided to go to court again. This time they were not targeting the creators of file-sharing tools, but the people who downloaded tracks.

This idea was controversial, also within the RIAA, and CEO Hilary Rosen even resigned over the matter.

“I didn’t want us to go against individuals, even though they were the source of a huge amount of illegal activity, I felt like ultimately they were still music fans. But essentially I was kind of overruled.

“My last day at the RIAA was the day before the litigation against individuals started,” Rosen adds.

The lawsuits became a trainwreck, especially because thousands of people seemed to be randomly targeted. Some may have been prolific downloaders, but the RIAA also sued ‘dead people,’ grandmas, and other unlikely targets.

Lawsuits Made Things Worse

Meanwhile, piracy wasn’t stopping. Stephen Witt, author of the book “How Music Got Free,” argues that the lawsuits only made things worse. This is corroborated by musician Nick Koenig, who was one of the RIAA’s targets at the time.

“I ended up having to pay like, I think close to a thousand dollars to the RIAA. But in the end, I ended up recouping my losses by downloading overtime and doubling down,” Koenig says.

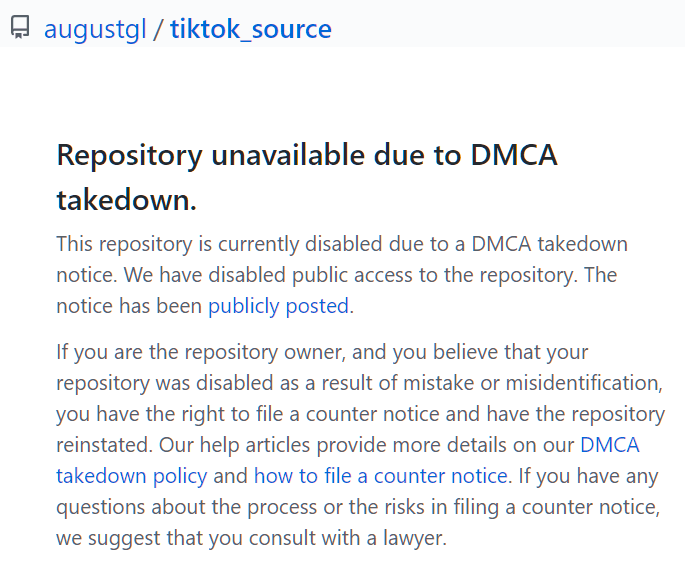

Around the mid-2000s the lawsuits had ended. It was the time when torrent sites started to dominate the piracy scene and these became even more popular when LimeWire shut down.

The Spotify Moment

A BitTorrent client named uTorrent became particularly popular, up to the point where its creator, Ludvig Strigeus, sold it. That money was then used for another startup that would shake up the music industry: Spotify.

When Spotify first went public in a few select countries in late 2008, we joined the ‘invite-only’ platform to see what it was all about. We were blown away .

Having all music tracks available for streaming was another Napster moment. Or perhaps it was better than Napster. It was the ‘celestial jukebox’ the music industry could only dream about a decade earlier.

Where’s The Money?

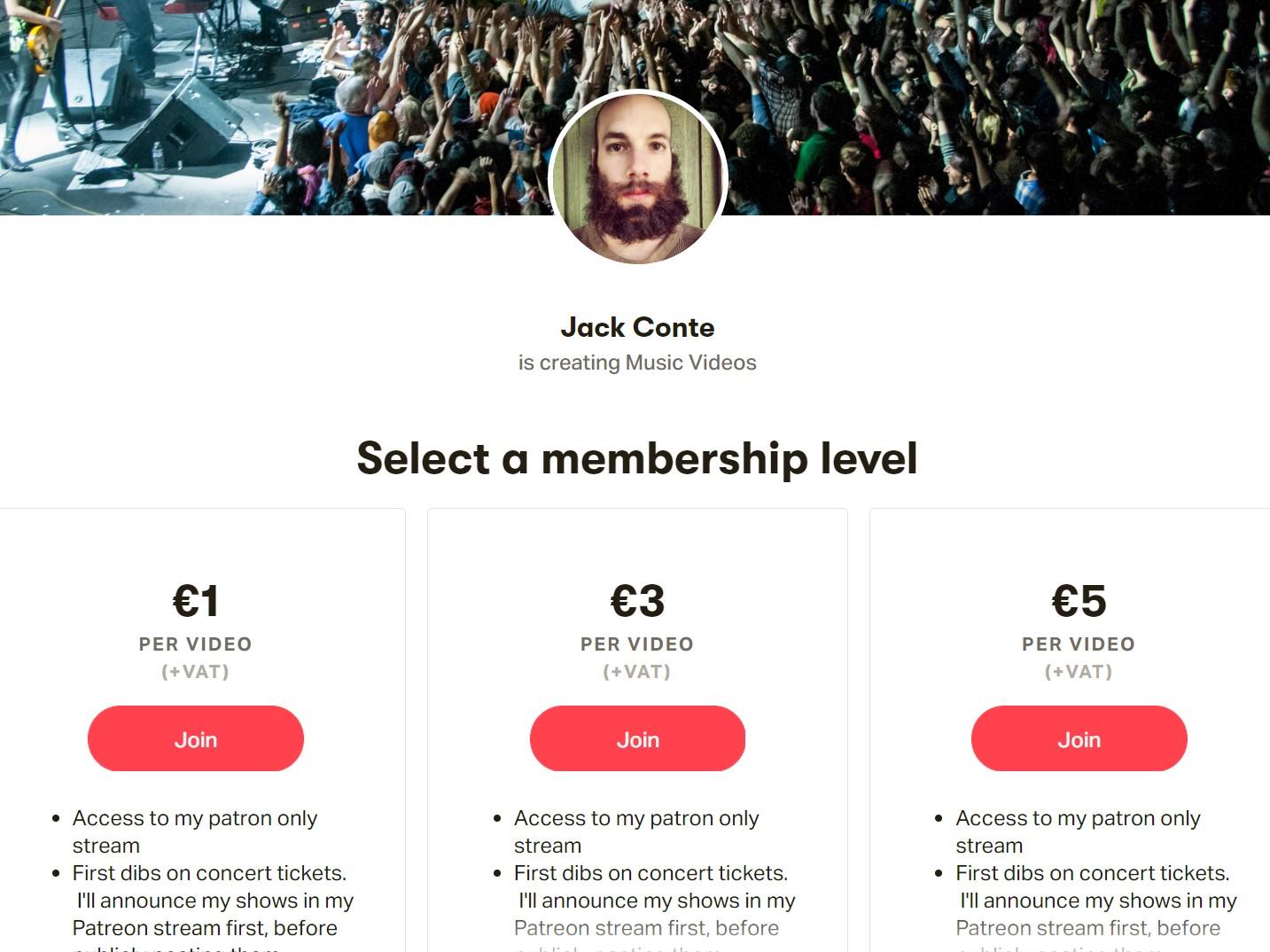

While Spotify and other platforms are great for users, not all artists are happy. Especially those who have to share a big chunk of their revenue with labels. But even for independent artists, the revenues are rather limited.

The documentary goes on to show how recorded music sales transformed from being the primary source of income to more of a promotional tool. Increasingly, musicians had to rely on other means such as concerts, merchandising, Bandcamp, or even Patreon to earn a decent living.

For older musicians, this isn’t easy. There’s an idea that music has lost its value. At the same time, unbundling and on-demand streaming are seen as desecrating the art of an album as a whole.

For labels, things have changed as well. Their monopolies are starting to crumble. While they still serve a purpose, artists are increasingly able to make it on their own. This is in part thanks to the many public outlets that are available today, where they can easily record, publish, and promote their work.

Those independent artists can keep more revenue for themselves. This is a topic we addressed in the past and in the documentary, rapper R.A. the Rugged Man brings this up too.

“It got to the point where I hated my label. So I said, Hey, I’m going to run and do this myself. And when I started doing independent records that’s when all my money started coming in. And that’s where all my success started coming in. And that’s where all of my fans started coming in.”

New Opportunities

At the same time, new technology also presents opportunities that, until recently, have never existed. For example, services such as Spotify can target concert promotions at a specific set of fans, be used to scout talent for festivals, and help users discover new content based on their musical taste.

New technologies also allow fans and musicians to get in direct contact. And without the middlemen, having 1000 passionate fans can already be enough to make a decent living, as DJ and music journalist Dani Deahl notes.

And who says that things will stop here? Streaming subscription platforms are the norm today, but these may be outdated again in the future. Looking back, it seems fair to conclude that piracy hasn’t destroyed the music industry, it mostly helped to get closer to the ‘celestial jukebox.’

The MP3 played a crucial role in this process. It was the catalyst that helped to shift the powers in the music business. This has hurt some companies and musicians, but also helped many others.

The “System Shock” documentary fittingly ends with a quote from the MP3’s co-inventor Karlheinz Brandenburg looking back, so we’ll do the same.

“I had the feeling, this is not good for the music industry. But in the end, I think it changed for the better,” Brandenburg says.

From: TF , for the latest news on copyright battles, piracy and more.

chevron_right

This week it was reported that Njord Law, a prominent Danish law engaged in cash settlement demands against alleged BitTorrent pirates, is in serious trouble.

This week it was reported that Njord Law, a prominent Danish law engaged in cash settlement demands against alleged BitTorrent pirates, is in serious trouble. Spearheaded by the RIAA, several major music industry companies have filed lawsuits against some of the largest U.S. Internet providers.

Spearheaded by the RIAA, several major music industry companies have filed lawsuits against some of the largest U.S. Internet providers.

Over the past several months, Danish law enforcement authorities effectively shut down the thriving local torrent tracker scene.

Over the past several months, Danish law enforcement authorities effectively shut down the thriving local torrent tracker scene. The idea to compress music into digital files started decades ago, but the birth of the MP3 was a breakthrough moment.

The idea to compress music into digital files started decades ago, but the birth of the MP3 was a breakthrough moment.

In 2018, a group of prominent record labels sued two very popular YouTube rippers,

In 2018, a group of prominent record labels sued two very popular YouTube rippers,  Over the past year, the Alliance for Creativity and Entertainment (ACE) added a new tool to its anti-piracy toolbox.

Over the past year, the Alliance for Creativity and Entertainment (ACE) added a new tool to its anti-piracy toolbox.