-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Archaeology is going digital to harness the power of Big Data

Jennifer Ouellette · news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Saturday, 2 January, 2021 - 23:10 · 1 minute

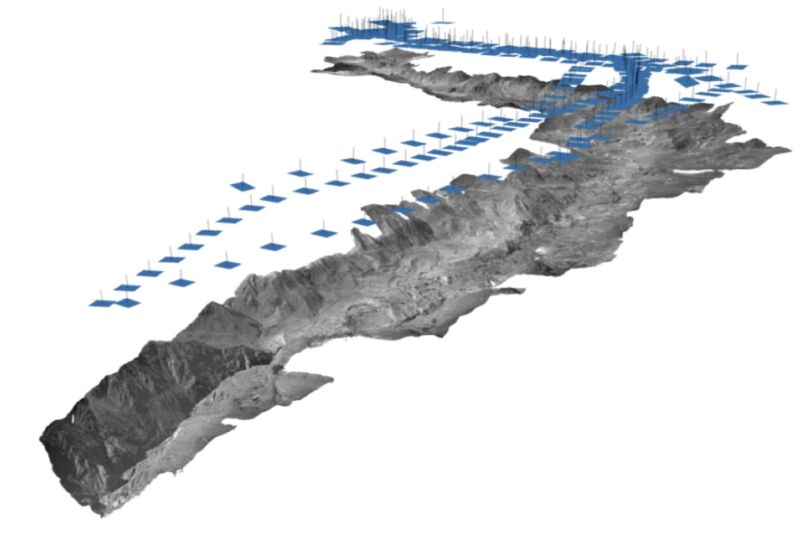

Enlarge / Archaeology is catching up with the digital humanities movement with the creation of large online databases, combining data collected from satellite-, airborne-, and UAV-mounted sensors with historical information. (credit: Brown University)

There's rarely time to write about every cool science-y story that comes our way. So this year, we're once again running a special Twelve Days of Christmas series of posts, highlighting one science story that fell through the cracks in 2020, each day from December 25 through January 5. Today: archaeologists are using drones and satellite imagery, among other tools, to build large online datasets with an eye toward harnessing the power of big data for their research.

Archaeology is finally catching up with the so-called "digital humanities," as evidenced by a February special edition of the Journal of Field Archaeology, devoted entirely to discussing the myriad ways in which large-scale datasets and associated analytics are transforming the field. The papers included in the edition were originally presented during a special session at a 2019 meeting of the Society for American Archaeology. The data sets might be a bit smaller than those normally associated with Big Data, but this new "digital data gaze" is nonetheless having a profound impact on archaeological research.

As we've reported previously , more and more archives are being digitized within the humanities, and scholars have been applying various analytical tools to those rich datasets, such as Google N-gram, Bookworm, and WordNet. Close reading of selected sources—the traditional method of the scholars in the humanities—gives a deep but narrow view. Quantitative computational analysis can combine that close reading with a broader, more generalized bird's-eye approach that can reveal hidden patterns or trends that otherwise might have escaped notice. The nature of the data archives and digital tools are a bit different in archaeology, but the concept is the same: combine the traditional "pick and trowel" detailed field work on the ground with more of a sweeping, big-picture, birds-eye view, in hopes of gleaning hidden insights.