-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Mathias Poujol-Rost ✅ · Sunday, 7 March, 2021 - 20:16

Contact publication

chevron_right

chevron_right

Mathias Poujol-Rost ✅ · Sunday, 7 March, 2021 - 20:16

Contact publication

chevron_right

chevron_right

Famous strange demises get a second look in The Curious Life and Death of…

Jennifer Ouellette · news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Thursday, 1 October, 2020 - 10:45 · 1 minute

Medical historian Lindsey Fitzharris hosts the Smithsonian Channel's new documentary series The Curious Life and Death of....

Infamous historical cold cases get a scientific face-lift in The Curious Life and Death Of... , a new documentary series from the Smithsonian Channel. Hosted by author and medical historian Lindsey Fitzharris , each of the six episodes takes a fresh look at a famous death with a mystery attached to it and sifts through the scientific clues to (hopefully) arrive at fresh insights.

Per the official synopsis:

Author and medical historian Dr. Lindsey Fitzharris will use science, tests, and demonstrations to shed new light on famous deaths, ranging from drug lord Pablo Escobar to magician Harry Houdini. Using her lab to perform virtual autopsies, experiment with blood samples, interview witnesses and conduct real-time demonstrations, Dr. Fitzharris will put everything about these mysterious deaths to the test. Along the way, she'll be joined by a revolving cast of experts, including Scotland Yard detectives, medical examiners, weapons gurus and more.

A noted science communicator with a large Twitter following and a fondness for the medically macabre, Fitzharris published a biography of surgical pioneer Joseph Lister, The Butchering Art , in 2017. (It's a great, if occasionally grisly, read.)

chevron_right

chevron_right

How the Warsaw Ghetto beat back typhus during World War II

Jennifer Ouellette · news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Sunday, 13 September, 2020 - 18:13 · 1 minute

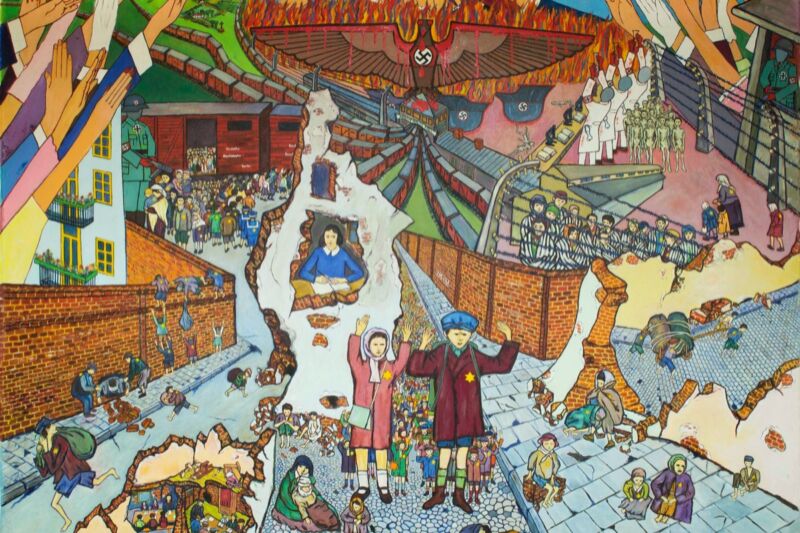

Enlarge / Painting by Israel Bernbaum depicting Jewish children in Warsaw Ghetto and in the death camps (1981). (credit: Monclair State University collection)

During the Nazi occupation of Poland during World War II, Jewish residents in Warsaw were forcibly confined to a district known as the Warsaw Ghetto . The crowded, unsanitary conditions and meager food rations predictably led to a deadly outbreak of typhus fever in 1941. But the outbreak mysteriously halted before winter arrived, rather than becoming more virulent with the colder weather. According to a recent paper in the journal Science Advances, it was measures put into place by the ghetto doctors and Jewish council members that curbed the spread of typhus: specifically, social distancing, self-isolation, public lectures, and the establishment of an underground university to train medical students.

Typhus (aka "jail fever" or "gaol fever") has been around for centuries. These days, outbreaks are relatively rare, limited to regions with bad sanitary conditions and densely packed populations—prisons and ghettos, for instance—since the epidemic variety is spread by body lice. (Technically, typhus is a group of related infectious diseases.) But they do occur: there was an outbreak among the Los Angeles homeless population in 2018-2019.

Those who contract typhus experience a sudden fever and accompanying flu-like symptoms, followed five to nine days later by a rash that gradually spreads over the body. If left untreated with antibiotics, the patient begins to show signs of meningoencephalitis (infection of the brain)—sensitivity to light, seizures, and delirium, for instance—before slipping into a coma and, often, dying. There is no vaccine against typhus, even today. It's usually prevented by limiting human exposure to the disease vectors (lice) by improving the conditions in which outbreaks can flourish.

chevron_right

chevron_right

Archaeologists may have found site of the Red Lion, London’s first playhouse

Jennifer Ouellette · news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Thursday, 11 June, 2020 - 18:41 · 1 minute

Enlarge (credit: Archaeology South-East/UCL)

Around 1567, a man named John Brayne built an Elizabethan playhouse called the Red Lion just outside the City of London to accommodate the growing number of traveling theatrical troupes. Its exact location has proven elusive to archaeologists—there were many streets and pubs named the Red Lion (or Lyon) over the ensuing centuries—but a team from University College London (UCL) believes they have found the original site at an excavation in Whitechapel.

The Red Lion is the earliest-known attempt to create a playhouse in the Tudor era, a precursor to the famed Globe Theatre . We know from historical documents—notably a pair of lawsuits involving Brayne's project—that it was a single-gallery multi-sided theater. A fixed stage was constructed, with trap doors and a 30-foot (9.1 meter) turret for aerial stunts. It was technically a receiving house for touring companies, as opposed to an actual repertory theater, and included the Red Lion Inn as part of its complex.

The Red Lion doesn't seem to have survived very long, perhaps because it was sited in open farmland and therefore only feasible for performances in the summer. Only one play seems to have been staged there, The Story of Samson . In 1576, Brayne partnered with his brother-in-law, actor/manager James Burbage, to build The Theatre at Shoreditch. (London banned plays in 1573 because of the plague—16th-century social distancing—which is why these early theaters were built outside the city's jurisdiction, in the so-called "suburbs of sin.")

chevron_right

chevron_right

Mass grave reveals how Black Death impacted rural England

Kiona N. Smith · news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Friday, 6 March, 2020 - 18:29 · 1 minute

Enlarge (credit: Willmott et al. 2020)

Archaeologists recently excavated a mass burial of at least 48 men, women, and children on the grounds of a medieval monastery in Lincolnshire, UK. One person’s teeth contained traces of bubonic plague DNA, and radiocarbon dating suggests that these people were victims of a 14 th century outbreak. It’s the first time archaeologists have found a mass grave for plague victims outside of a city like London or Hereford, and it reveals that even small country villages struggled to bury the masses of plague victims.

University of Sheffield archaeologist Hugh Willmott and his colleagues didn’t expect to find skeletons when they dug a trench on the grounds of Thornton Abbey. They thought the geophysical anomaly they were preparing to excavate was part of a 1607 mansion built nearby. But instead, they wrote, “the excavation immediately revealed articulated human skeletal remains.” The dead lay in rows, packed so closely that they’d have been touching, with the feet of one row lying between the heads of the next.

Even more surprisingly, the skeletons included at least six women and 21 children, so they definitely weren’t all monks from the abbey. The 48 bodies in the wide, shallow grave probably included people from the surrounding countryside who died at St. James hospital, adjacent to the monastery. In fact, the grave might have held nearly half the 14 th -century population of the surrounding parish, all buried together.