-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Unexpected chemical found in Venus’ upper atmosphere

John Timmer · news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Monday, 14 September, 2020 - 21:03 · 1 minute

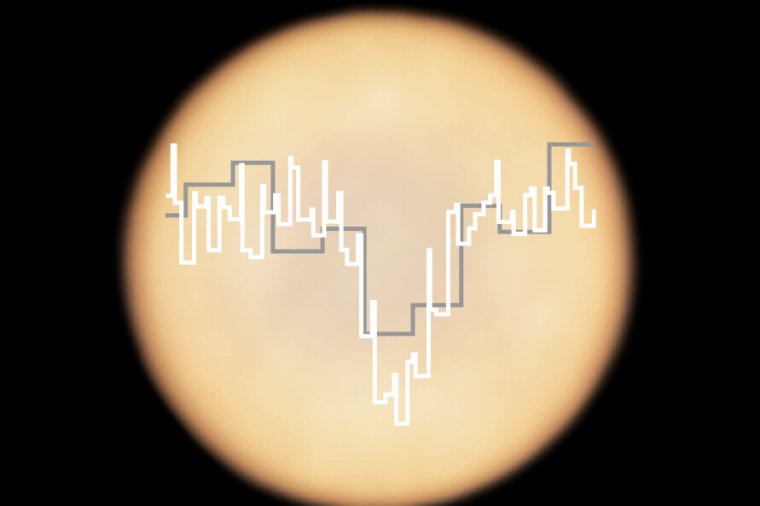

Enlarge / The spectral signature of phosphine superimposed on an image of Venus. (credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), Greaves et al. & JCMT )

Today, researchers are announcing they've observed a chemical in the atmosphere of Venus that has no right to be there. The chemical, phosphine (a phosphorus atom hooked up to three hydrogens), would be unstable in the conditions found in Venus' atmosphere, and there's no obvious way for the planet's chemistry to create much of it.

That's leading to a lot of speculation about the equally unlikely prospect of life somehow surviving in Venus' upper atmosphere. But a lot about this work requires outside input, which today's publication is likely to prompt. While there are definitely reasons to think phosphine is present on Venus, its detection required some pretty involved computer analysis. And there are definitely some creative chemists who are going to want to rethink the possible chemistry of our closest neighbor.

What is phosphine?

Phosphorus is one row below nitrogen on the periodic table. And, just as nitrogen can combine with three hydrogen atoms to form the familiar ammonia, phosphorus can bind with three hydrogens to form phosphine. Under Earth-like conditions, phosphine is a gas, but not a pleasant one: it's extremely toxic and has a tendency to spontaneously combust in the presence of oxygen. And that later feature is why we don't see much of it today; it's simply unstable in the presence of any oxygen.