-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Million-year-old mammoth DNA rewrites animal’s evolutionary tree

John Timmer · news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Wednesday, 17 February, 2021 - 18:10 · 1 minute

Enlarge / A mammoth tusk thaws out of the ground in Siberia.

Ancient DNA has revolutionized how we understand human evolution, revealing how populations moved and interacted and introducing us to relatives like the Denisovans, a "ghost lineage" that we wouldn't realize existed if it weren't for discovering their DNA. But humans aren't the only ones who have left DNA behind in their bones, and the same analyses that worked for humans can work for any other group of species.

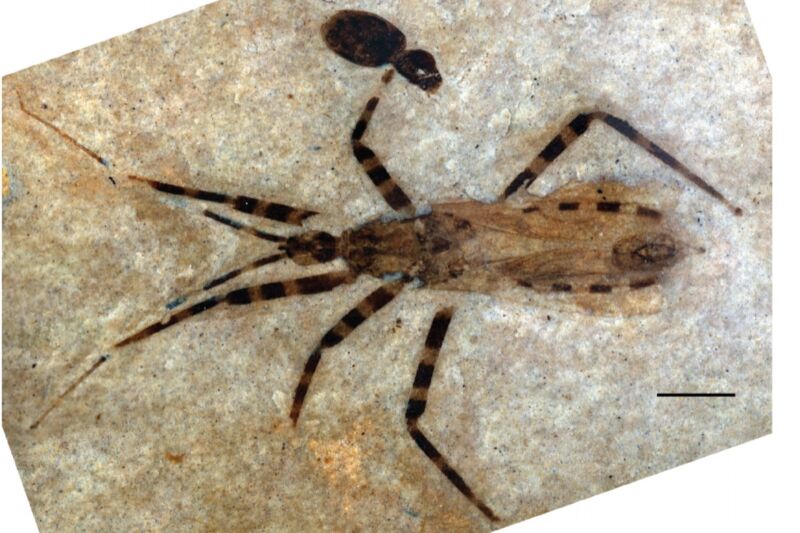

Today, the mammoths take their turn in the spotlight, helped by what appears to be the oldest DNA ever sequenced. DNA from three ancient molars, one likely to be over a million years old, has revealed that there is a ghost lineage of mammoths that interbred with distant relatives to produce the North American mammoth population.

Dating and the mammoth family tree

Mammoths share something with humans: like us, they started as an African population but spread across much of the planet. Having spread out much earlier, mammoth populations spent enough time separated from each other to form different species. After branching off from elephants, the mammoths first split into what are called southern and steppe species. Later still, adaptations to ice age climates produced the woolly mammoth and its close relative, the North American mammoth, called the Columbian mammoth. All of those species, however, are extinct, and the only living relatives are the elephants.