-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Teacher with COVID symptoms went maskless, making her class an experiment

John Timmer · news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Monday, 30 August, 2021 - 21:06 · 1 minute

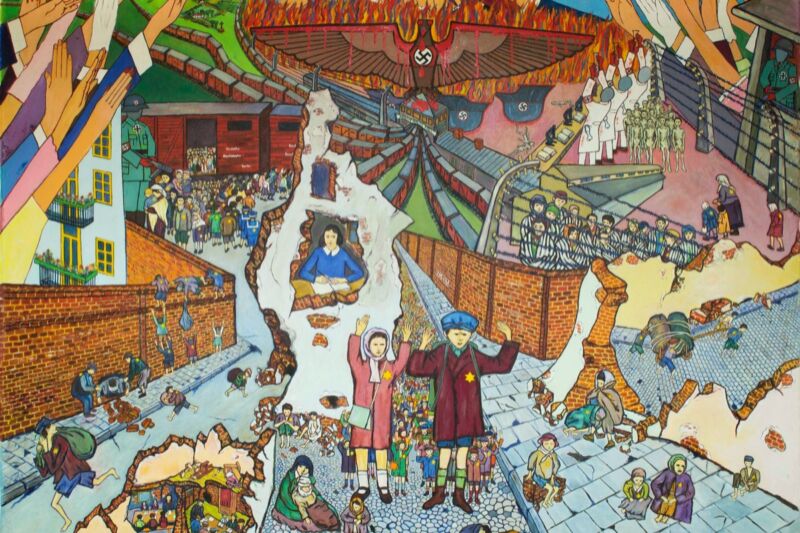

Enlarge / Two classrooms had to be shut down due to a series of problems with maintaining policies meant to limit the spread of the pandemic. (credit: Andrew Lichtenstein / Getty Images )

On Friday, the CDC released a report that traced the spread of the Delta variant through a California elementary school. It's tempting to make this into a story of gross irresponsibility—a teacher was unvaccinated and read to the class while unmasked. But beyond that, it provides a number of warnings about how our public health system remains under stress as we close in on two years since the start of the pandemic. It also reemphasizes how the Delta variant ensures that small errors can easily explode into big problems.

One bad apple

The school in question was a small one, with only a bit over 200 students and 24 staff. It is an elementary school, meaning that its student population is also younger than the cutoff for approved vaccine use. The school did a number of things right, though. Class sizes were kept small, and individual classes were kept in separate rooms, with doors and windows kept open and air filtration equipment installed. There was also a standing policy requiring mask use in place.

But not everything was ideal. The CDC notes that two of the 24 staff members were unvaccinated. While the vaccinated can clearly transmit the Delta variant, they are likely to be less infectious, and in a worst case they'd be infectious for a shorter period of time.