-

chevron_right

chevron_right

BA.2.86 shows just how risky slacking off on COVID monitoring is

news.movim.eu / ArsTechnica · Monday, 21 August, 2023 - 20:17

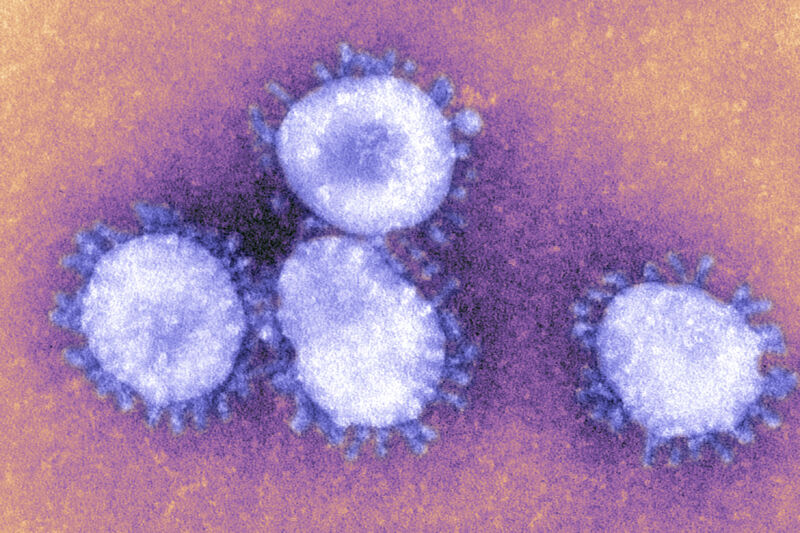

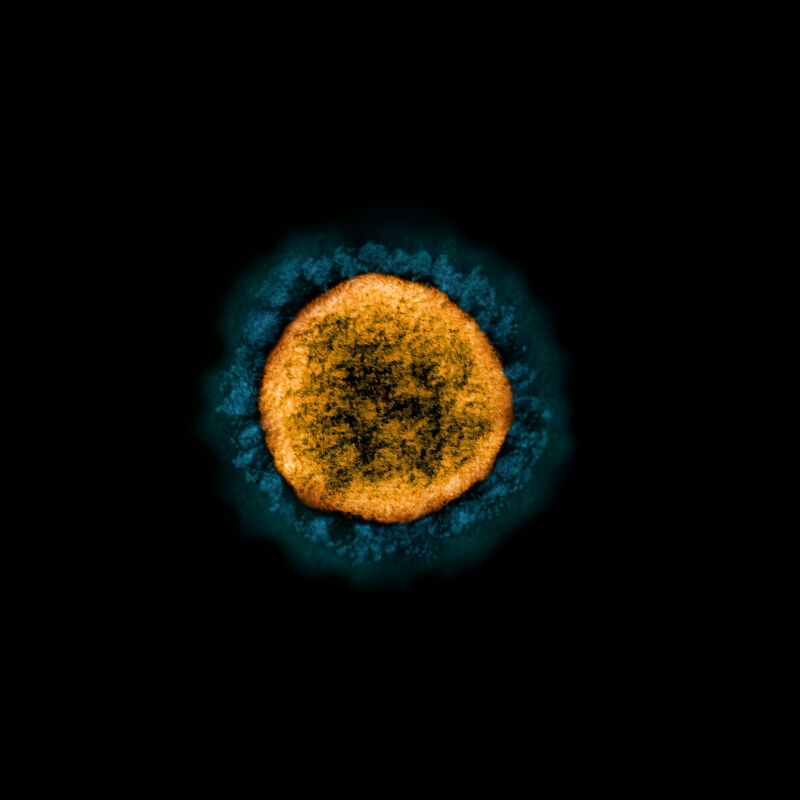

Enlarge / Transmission electron micrograph of a SARS-CoV-2 virus particle isolated from a patient sample and cultivated in cell culture. (credit: Getty | BSIP )

A remarkably mutated coronavirus variant classified as BA.2.86 seized scientists' attention last week as it popped up in four countries, including the US.

So far, the overall risk posed by the new subvariant is unclear. It's possible it could lead to a new wave of infection; it's also possible (perhaps most likely) it could fizzle out completely. Scientists simply don't have enough information to know. But, what is very clear is that the current precipitous decline in coronavirus variant monitoring is extremely risky.

In a single week, BA.2.86 was detected in four different countries, but there are only six genetic sequences of the variant overall —three from Denmark, and one each from Israel, the UK, and the US (Michigan). The six detections suggest established international distribution and swift spread. It's likely that more cases will be identified. But, with such scant data, little else can be said of the variant's transmission or possible distribution.